Talking with a Nicaraguan friend about the situation in his home country, I recently commented on an instance of cultural transfer I thought might be interesting in that particular moment, but maybe not of any wider significance. Yet, whilst talking, I somehow became curious if it had been noticed before; and after a cursory search on the internet yielded no results, I thought I might as well scribble some thoughts about it down here.

The topic of conversation between my friend and me was about the necessity of directed action in the fight against authoritarian rulership. The opposition forces in Nicaragua attempt to build a coalition at the moment, thereby following Gene Sharp’s From Dictatorship to Democracy in its outline. That seems all well and feasible with me, but in that particular conversation I was wondering if a more multipolar approach that defies directedness (let alone Leninist party politics) can achieve the same results. For Sharp it seems that it doesn’t, as he advocates the build-up of a unified front (without calling it that) and regards multipolarity as a weakness that eventually needs to be overcome.

Incidentally, that watershed between uni- and multipolarity connected in my mind with the curious case of the song L’Estaca and its transnational meanderings. That song was composed by Catalan songwriter Lluis Llach in 1968. Its lyrics in the Catalan language meant that it was censored during Francisco Franco’s dictatorship, and Llach’s performance of the song in the Palau de la Música Catalana in 1976 – in which he defiantly sang the Catalan lyrics shortly after Franco’s death – for many marked the beginning of the transición (maybe only firmly established after the suppression of the attempted coup d’état in 1981).

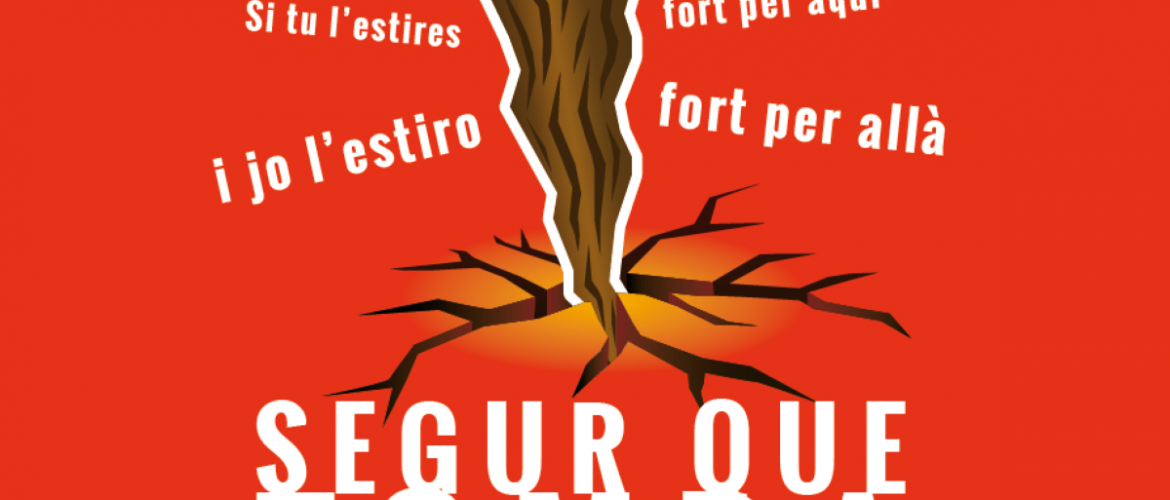

The lyrics of the song metaphorically speak of a pole or stake (Cat.: l’estaca) to which many others are forcedly bound. The song’s lyrical persona listens to a wise old man who advises that all the people tied to the pole should start moving to dislodge it:

Si estirem tots, ella caurà

i molt de temps no pot durar,

segur que tomba, tomba, tomba

ben corcada deu ser ja.

Si jo l’estiro fort per aquí

i tu l’estires fort per allà,

segur que tomba, tomba, tomba,

i ens podrem alliberar.

Meaning in English translation:

If we all pull, it will fall

and it will not endure for long,

it is sure that it falls, falls, falls,

it should already be well rotten.

If I pull hard here,

and you pull hard there,

it is sure that it falls, falls, falls,

and we can liberate ourselves.

A powerful image of concerted, collective yet not unidirectional action: All suppressed follow the same plan, all pull, but into various directions. The image of the stake as the centralised power structure actually necessitates such a form of disruption.

In the lyrics there is no leader, just an advisor, a voice that implies (and maybe implores), an observer that presumes the stake already is rotten from the inside. The political implications of this imagery become clear even without knowing that the Catalan word for “the state” is “l’estat,” closely resembling “l’estaca.”

Although the song was banned throughout Spain, it become quite well-known in opposition circles in different countries, and around 1978 Polish songwriter Jacek Kaczmarski composed new lyrics in Polish to the song. His version, titled Mury (Walls), became an anthem of Solidarnosc, the labour-union-cum-political-movement.

Kaczmarski’s lyrics, though, totally transform the images of oppression and resistance. They centre on a singular leading figure who, by its singing, forges the masses into a unified group. The Polish song – in English translation – starts:

Young and inspired he was. They were numberless.

He gave them strength with his song, singing of the nearing dawn.

In “Mury” the masses are not tied to a pole, but infringed by walls, thus transposing the submission from one central point to four directions. The people’s weakness is their inability to see their commonly shared desires and their shared infringement. Only thanks to the images created by the singer’s song, they realise their group identity:

At last they saw the number of them, they felt their strength, their time

and they start to march with the “boom of their steps” in one direction, tearing the shackles from the walls so that they’ll “fall, fall, fall / And they’ll bury the old world!”

Clearly, for a hierarchical movement like the trade-union-based Solidarnosc, such images carried further than the grassroots-orientation of Llach’s original. And the Polish movement has had a deeper direct impact on their country’s politics than the Catalan independence movement has had so far (which doesn’t mean that Llach composed “L’estaca” as a call for independence). Does that mean advocating unified action at all occasions? Obviously, that’s something every political organization has to deal with in its time and space; L’estaca and Mury are just two auditory embodiments of – at least two – different approaches to overthrowing authoritarian institutions.

Furthermore, the transcultural trajectory of the song – or songs? – in my view is a strong reminder what translation actually means: the adaption of words, images and sounds into different contexts, always gaining and losing certain significances.